In Rome, physicians who had come from Greece to care for the new masters of the world developed a theory and practice of psychiatric treatment, the tradition of which continued into the 19th century.

* Lire en français.

Is it possible to speak of "psychiatry" in the context of antiquity, and to apply to early history a word that didn't appear until the early 19th century? By coining a new term from notions drawn from ancient Greek (psychè, the soul, and iatreia, medicine), early modern alienist physicians intended to give a new name to the specialty that was then developing in new institutions: asylums for the "insane". In this sense, the invention of the neologism marked a break with a medical tradition that knew neither places nor professionals dedicated to the care of the mentally ill.

Yet there can be no doubt that ancient societies recognized their own "madmen" as patients. The physicians of Greco-Roman Antiquity set out to care for them and to consider their illnesses in all their diversity. Integrated into general medicine, this therapy already had its own concept: curatio furiosi, i.e. "care of the demented". With such a formula, ancient medicine was expressing its concern not to remedy disorders of the "soul" - a notion foreign to its field of competence - but the disorders of certain individuals - those whose mental faculties were seriously affected.

A Roman revolution

During this period, the Roman era was not just another moment in the history of psychiatry, but one that gave rise to a more or less revolutionary founding gesture. Prior to this, among the peoples and cities of the archaic and classical Mediterranean (8th-4th centuries BC), the severe psychic disorder that the Greeks called mania and the Latins furor, gave rise to a special legal regime, justified by the degraded state of health of the people it affected. However, its medical status was that of a handicap, rather than an illness: while it called for accommodations and a caring attitude, its nature rendered impotent the remedies employed at the time to cure illnesses.

On the contrary, between the Hellenistic and Roman periods (2nd century BC - 2nd century AD), occurred a break in the supply and demand for healthcare. Under new geopolitical, economic, social and technical conditions, the Greek-based medicine practiced in Rome, the new capital of the Mediterranean world, broadened its claims and extended its field of intervention. It was against this backdrop that the care (cura) traditionally given to the "insane" developed into genuine medicine (curatio), and something like psychiatry was born.

Ancient psychiatry

By the 1st century BC at the latest, ancient psychopathology was organized around three main concepts, which would continue to shape the classification of mental illnesses until recent times. "Phrenitis", an acute illness accompanied by fever, often fatal after only a few days, originated in prehistoric times. Received by Hippocratic medicine from an earlier oral tradition, it forms the cornerstone of psychopathology: it's what doctors speak of most readily, because it is overwhelmingly and manifestly a disease of the body; some patients show no psychic symptoms at all. "Mania", whose category and name seem to derive from the social and legal sphere, is then conceptualized in relation to phrenitis: on the basis of a common sign (psychic disorder, which becomes necessary in phrenitis), "mania" is defined by the absence of the other signs of the first concept (fever, acute and fatal character). In a second move, "melancholy" is conceived from a poetic image, again in a relationship of distinction with mania: whereas the latter disturbs perception or reason, melancholy affects not so much the senses and judgment as feelings and emotions.

Medical theories in general - and psychiatric ones in particular - are the subject of well-documented subtle controversies. Some say it is due to an imbalance of the humours (blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile), others to the flow of vital breath (pneuma), still others to the movement of the atoms that form the body and animate it... Carefully studied by the history of psychiatry, these debates can be perplexing, but should not obscure other elements of consensus, which deserve at least as much attention. Most medical authors accept a cerebral and nervous anatomy - with a co-implication of the digestive system in melancholia - and acknowledge that the most characteristic psychic disorders, mania and melancholia, have both exogenous and endogenous factors, both bodily and psychic ones.

Overall, theories are the shadow of the treatment methods adopted by ancient practitioners. Among them, surgery was not used to treat "madness" - despite the medieval myth of the "stone of madness" and the prejudice fostered by the recent use of lobotomy, unknown to the ancients. As "internal" illnesses, mental illnesses are essentially treated by purging bodily fluids, through various means (bloodletting, enemas, vomiting, etc.), the effect of which is also to exhaust the body. As lifestyle diseases, they give rise to a "regime", simultaneously a diet and an exercise program, making psychiatry a discipline of the body.

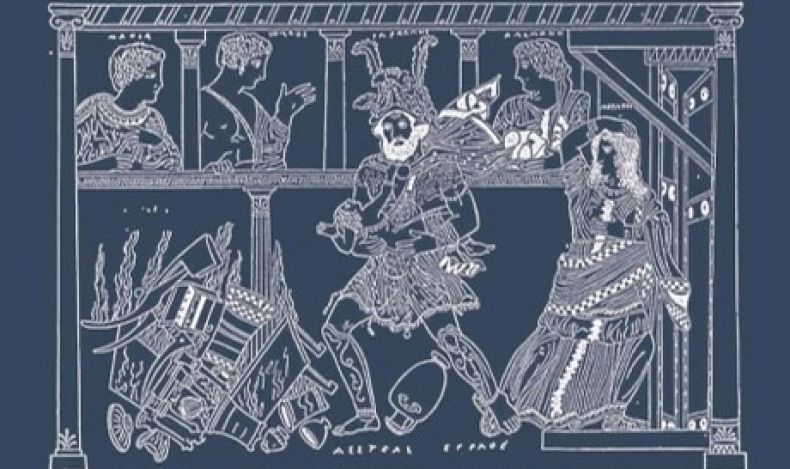

Within this program, various provisions and exercises are aimed at the senses (prescription of theater, proscription of music or visual arts...). Others are more directly thought-provoking (dialogues, readings, recitations, etc.). Taken together, they constitute the elements of "psychotherapy". But psychiatric care also relies on a spectrum of drugs, about which doctors are less forthcoming, because pharmacopoeia is the specialty of a competing profession. At the end of the book, an annotated glossary reviews the various therapeutic acts and remedies employed: the use of restraint and violence, sedatives and psychotropic drugs, hellebore and massage...

Celsus and Caelius Aurelianus

Above all, La Psychiatrie à Rome offers translations in French of three texts of major importance to our knowledge of ancient psychiatry. The first was written by Aulus Cornelius Celsus, a Roman aristocrat and author of a vast encyclopedia covering all the fields of knowledge that should form the culture of a great landowner (law, rhetoric, military art, agriculture...). The care of both animals and human dependents was part of the family head's duties, so that the medical treatment (curatio) of "insane" relatives was the corollary of their guardianship (cura). Of this sum, the books on medicine are the only ones to have survived. A blend of Hippocratic theory and Methodist practice (named after a school that partly opposed Hippocratic teaching), Celsus' text is the expression of a certain Roman pragmatism. It is interesting in that it offers the first evidence of the invention of psychiatry by this Methodist school, a century after its invention and in a synthetic form. Its originality lies in the fact that it proposes a generic concept of "psychopathology", unifying phrenitis, mania and melancholia under the same category of "madness" (insania). Although Celsus did not initiate this operation, it stands out all the more in his secular, didactic and Roman perspective.

But the physician Caelius Aurelianus provides an infinitely richer account in the chapters he devotes to mental illness in his treatise on Acute Diseases, then in his treatise on Chronic Diseases published a few years later. The excerpts from these books form by far the most substantial contribution to the history of psychiatry in ancient literature. All the more so as they offer both a comprehensive account of medicine - examining categories, theories and remedies - and a historical account of its development. The mysteries of these books are commensurate with their richness, since although Caelius wrote his texts in the twilight of antiquity (between the 4th and 5th centuries AD), they appear to be essentially translations of books written in Greek by the physician Soranos of Ephesus in the 2nd century AD. Transcribed into Latin, but also adapted to the Roman cultural universe, with references to Cicero and Virgil, they offer the most accomplished vision of mature Greco-Roman psychiatry. A remarkable theoretical and practical edifice, passed down to posterity in a more or less fragmentary and renewed way, right up to the alienism that was the ancestor of "our" psychiatry.