An exploration of the historical context that led France and the United States to compete for a position at the centre of artistic and cultural renewal after the Second World War.

* Lire en français. The English translation is provided by the editorial staff, who are solely responsible for any inaccuracies.

In 1999, art historian Serge Guilbaut published Comment New York vola l'idée d'art moderne (ed. Jacqueline Chambon), offering a new reading of twentieth-century art history, and analysing in particular the links between the two continents that shaped it, Europe and North America. The book has even been shown in numerous exhibitions as a mirror image of the works of art involved.

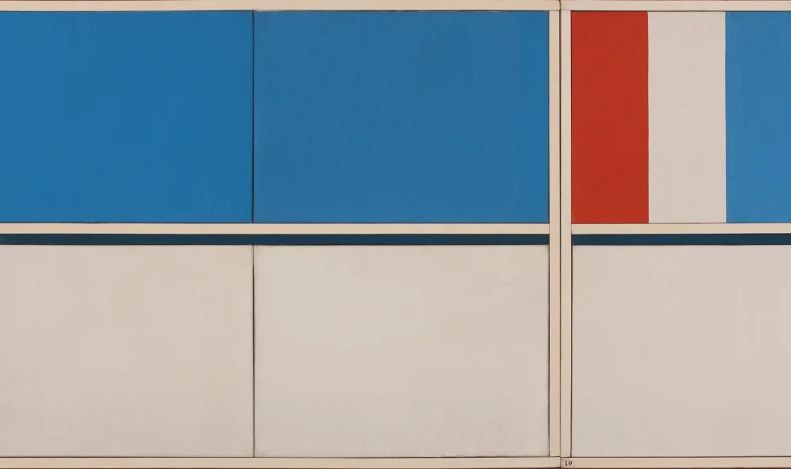

In this richly illustrated edition, the author continues this work by studying the cultural and political relations between France and the United States that led Paris, symbol of industrial modernity in the nineteenth century, and New York, emblem of the new consumer society, to transform themselves in the aftermath of the Second World War.

Cultural "ping-pong"

The end of the war brought with it the need to rebuild the cultural life of both countries. Paris, for its part, was seeking to regain its old image as a progressive city and a universal creative centre. A new generation of artists such as Bram Van Velde, Samuel Beckett and Wols were looking to art to provide a human face in a world sorely lacking one. New York, for its part, sought to conquer the hegemony hitherto held by the Europeans, by unfolding the dream of rebuilding an independent political and cultural space.

It was a game of "ping-pong" between the two capitals, and Guilbaut's method of studying the period is well suited to this: he takes the view that the history of twentieth-century art takes shape on the basis of cross-influences, shifts in perspective, debates and controversies on both sides of the Atlantic.

However, this does not mean neglecting the forces that were attempting to challenge the aesthetic choices of the Western world at the same time. Guilbaut draws on recent work that has highlighted the hitherto neglected deployment of modern art in provincialised regions of the world, such as South America and India.

The author also looks at the efforts being made within Western society to transform the foundations of bourgeois society, tainted by the crimes of the Occupation, and to envisage a new society. In this sense, he analyses the political options that sought to win over public opinion but were ultimately limited to intellectual circles, such as socialism, supported in France by the PCF.

From this point of view, work on the archives is crucial, and Guilbaut's work has benefited from consultation of long-inaccessible or private archives such as those of Cassou, Jaguer, Koots and Hartung, and even those of various ambassadors. The book also includes an extensive bibliography and copious notes commenting on various documentary materials (articles, reviews, films, letters).

In short, the author's historiographical method steers clear of any simplification or univocal interpretation: the history of art that emerges breaks with the canonical account of this period in many respects, and demystifies certain judgements or characters that are usually glorified.

The struggle for artistic modernity

With the Cold War and the growing rivalry between the American and Soviet powers, the question arose as to France's place in the world and its latitude for cultural renewal. The author describes in detail the situation of writers and artists during this period, driven both by the painful memory of the Occupation and by the impetus of the Resistance — the PCF actively supporting these artists' attempts to regain control of culture.

Guilbaut devotes a detailed examination to Picasso's works, and in particular to the painting "L'homme à l’agneau" ("Man with a Lamb"), highlighting the ambiguities of the period. He also comments on Jean Fautrier's "Otages" ("Hostages") series, underlining how difficult it is for the viewer to understand these paintings independently of their charged historical context.

From a technical point of view, this situation led artists in particular to adopt an expressive aesthetic, in which colour took on meaning and importance in its own right. This was part of a wider search for new ways of seeing, representing and bearing witness in a world that was essentially grey, politically and morally divided, and dominated by Vichy academicism.

The author details the specifics of the French historical situation, highlighting both the enthusiasm generated by this cultural renaissance — which quickly attracted great intellectuals, then withered as political unity disintegrated — and the ambivalence of the way it was viewed abroad.

In the United States, people were closely following what was going on in Paris and trying to find out about the latest discoveries by Parisian artists. Some looked on them with disdain, considering them to have become mere entertainers, creators of "tangy visual candies" — to use the expression of art critic Clement Greenberg. Guilbaut notes that this American blindness to post-war French art had its counterpart in France, since American works were not really taken seriously on the Old Continent. Jean-Paul Sartre's trip across the Atlantic, commented on by the author, is illuminating in this respect.

In a way, each of the two camps is trying to claim a kind of 'modernity patent' for itself.

Political and economic issues

This cultural rivalry took place in a very specific context, which placed the United States and France in an asymmetrical relationship. The war had reorganised political and economic forces at international level, and the United States was emerging as an essential support for the reconstruction of Europe. In this context, Guilbaut takes a close look at the strategy adopted by France and the way it negotiated with American power: it had to take the help of its American ally without allowing itself to be caught up in its network of influence, and let it impose itself as the undisputed leader of Western civilisation.

Artistic renewal and the redefinition of French cultural identity must be understood in the light of these facts, between the temptation to follow the American Way of Life and the desire to enhance France's cultural independence. The author's in-depth commentaries on the works of this period provide original interpretations that show the ambiguity of these relationships and the complexity of the exchanges and influences that took place on both sides of the Atlantic. Similarly, some of the fashion shows that provoked scandal, or certain exhibitions manoeuvred by governments, are placed in the strategic context of repositioning on the international stage.

From this point of view, the case of cinema occupies an important place. Guilbaut describes the intense war of images that was being waged at the time. On the one hand, Hollywood cinema arrived in Europe with the clear aim of spreading a certain lifestyle, promoted by a country that set itself up as a symbol of freedom. On the other hand, French cinema, which was undergoing reconstruction, was trying to maintain its autonomy, and critics such as Georges Sadoul were quick to denigrate American productions.

In the light of the criticisms and polemics launched from one continent to the other, Guilbaut succeeds in subtly restoring the way in which the United States and France judged, criticised, but also received and reworked each other's artistic productions, shedding new light on the game of "ping-pong" that structured the history of art in the second twentieth century.