J-J. Lecercle analyses Lenin's writings through his practice and conception of language. He shows the extent to which the revolutionary leader wielded language as a political weapon.

* Lire en français. The English translation is provided by the editorial staff, who are solely responsible for any inaccuracies.

Re-reading Lenin in our time may seem unusual, even daring, given the current political, theoretical and historical climate, which tends to relegate his works and ideas to a long-gone past.

For Jean-Jacques Lecercle, there are many reasons to (re)read Lenin today. Firstly, from a political point of view, he allows us to rethink the strategies of revolution and the seizure of power in the face of capitalism and state apparatus, which must still be broken. Secondly, from a historical perspective, Lecercle analyses our present times in the light of their most marked crises (the acceleration of the climate crisis, the multiplication of imperialist wars, the resurgence of fascism) and draws parallels with Lenin's time. Finally, from a philosophical point of view, reading Lenin's writings helps to rectify the image that doxa attributes to him.

But Jean-Jacques Lecercle, honorary university professor and specialist in the philosophy of language, takes a slightly different approach to this author, focusing on his discursive activity. Rather than the political strategist and leader, this book focuses on the polemicist, the orator and the prolific writer of articles.

More generally, the author challenges the view that Lenin's thought is out of date: the study of Lenin's relationship with language is an opportunity to examine language practices in political struggles (including today's), of which Lenin is a particular example.

Language as a political object

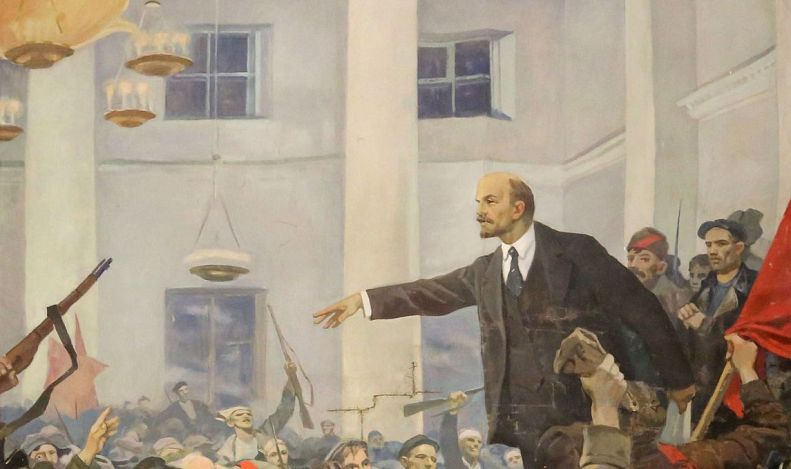

Lecercle's starting point is Aristotle's famous assertion that man is a "political animal" insofar as he is a speaking being. From this perspective, language is not only a decisive strategic weapon, but also an essential part of political activity itself. Lenin's use of language was thus part of a powerful political strategy that placed him directly at the heart of the political arena.

More specifically, the author highlights the capacity of language to interrupt the political game: the revolutionary's discursive practice makes it possible to break the symbolic logic of the dominant class, which considers language to be a simple instrument of communication. Lenin, on the other hand, believes that language is always a vehicle for ideology, and is therefore shaped by politics.

To develop these aspects, Lecercle draws on a reading of Jacques Rancière and his redefinition of politics. For Rancière, the spoken word is the foundation of politics, because it enables us to move from affect to concept, to a shared network of meaning, and in particular to a concept of justice.

Language is thus the site of an ideological struggle which, from a communist perspective, can be related to the class struggle. Far from the theory of communicative action forged by Jürgen Habermas, Lenin admits that it is in the context of language practices that the relations of power in societies crystallise.

The politics of watchwords

By highlighting this theory of language agonistics, Lecercle invites us, via Lenin, to rethink the current uses of language. As a collective system, language is beyond the control of the individual speaker; but at the same time, it is at the heart of processes of subjectivation through interpellation and counter-interpellation.

In this in-between situation, each individual is both assigned to a language and in a position to escape that assignment by manipulating and reworking the language that precedes him. Insofar as language is a practice, the use of speech is always an opportunity to subvert language — or at least to subvert its dominant usages.

A text by Lenin from 1917 dealing with the notion of the "watchword" illustrates this idea particularly well. The watchword is a linguistic object that cannot be adequately studied by a purely technical analysis of the language that formulates it. To understand its uses and effects, it is necessary to take account of the context in which it is used. In other words, a watchword does not exist in itself; its meaning is always 'in situation'. And what it says is intended to exert a force, to transform social relations.

A text by Lenin from 1917 dealing with the notion of the "watchword" illustrates this idea particularly well. The watchword is a linguistic object that cannot be adequately studied by a purely technical analysis of the language that formulates it. To understand its uses and effects, it is necessary to take account of the context in which it is used. In other words, a watchword does not exist in itself; its meaning is always 'in situation'. And what it says is intended to exert a force, to transform social relations.

Lecercle also examines Lenin's proposals for language policies. In the context of Russia at the time, these relate in particular to the relationship with independence movements that wanted to impose a national language for each people of the Empire.

In other texts by Lenin, the author raises the question of the discursive practice of activists, the relationship between language and truth — in other words, propaganda — and the specificity of literary language. As a linguist, Lecercle presents these issues clearly, leading the reader to see language as more than a system of signs, as a genuine political practice.