Dominique Missika traces the career of the Jewish producer whose success was interrupted by the rise of anti-Semitism, and who was murdered in Auschwitz.

* Lire en français. The English translation is provided by the editorial staff, who are solely responsible for any inaccuracies.

In times of ideological plague, no book is more necessary than this one: Dominique Missika's meticulous investigation does justice as well as truth, restoring dignity to the visionary producer and filmmaker Bernard Natan. This penniless immigrant from Romania built the film studios on rue Francoeur and others in Joinville-le-Pont, as well as luxurious, vast projection rooms and printing laboratories. He hired the best directors, screenwriters and technicians. He produced feature films with all the big stars of the day. In fact, Natan was one of the main creators of the French film industry between the wars.

He spent his youth in Yassy, Romania's second-largest city, where the poet Benjamin Fondane (1898-1944) was also born. He did not wear the yellow star, was arrested by the Vichy police, handed over to SS officer Dannecker's Gestapo, interned at Drancy, deported and murdered at Auschwitz-Birkenau in May 1942. Yassy was also home to the legendary conductor and composer Sergiu Celibidache (1915-1996). From June 28 to July 6, 1941, Yassy was the scene of the atrocious pogrom instigated by fascist dictator Ion Antonescu, which claimed the lives of 12,000 Jews and was recounted by Curzio Malaparte in Kaputt.

Growing up in anti-Semitic Romania

Nahum Tanenzaph, his real name, was born in the center of the city, where his parents ran a crystal store. He studied chemistry at university, while taking an interest in motion photography and cinematography. As in Ukraine, Russia, Poland, Lithuania and Latvia, anti-Semitism reigned in Romania, where Jews were hounded in the streets and persecuted in university lecture halls. Nahum dreamed of France, the "fatherland of human rights".

Between 1880 and 1914, Jews emigrated en masse to the United States, Germany and France. Like many Romanians, Tanenzaph spoke impeccable French when he arrived in Paris in 1906. After settling in Maisons-Alfort, he found a job washing films at the Pathé-Frères laboratories in Joinville-le-Pont, before being hired as a projectionist in Paris, where he met a woman who was five years his senior and a head taller. Her name was Marie-Louise Chatillon. He married her on December 14, 1909 at the town hall in the 18th arrondissement in Paris.

Nahum soon embarked on a business venture, teaming up with two friends to set up Ciné Actualité, a company specializing in "the manufacture and publication of photographic films and the sale of films and related equipment".

Cinema has just come into being

Charles Pathé opened the Omnia cinema on Boulevard Montmartre in 1906. Two hundred and fifty seats. Red velvet armchairs and gilded panelling, just like at the theater. Then, in 1911, Léon Gaumont built the Gaumont Palace on Place Clichy. It was then the largest theater in the world, with three thousand five hundred seats. It screened Judex, Fantômas and Les Vampires, directed by Louis Feuillade.

Nahum and his associates rented a studio in Maisons-Alfort, hired reporters and produced the "animated illustration of the week", which they offered to rent to exhibitors. Gaumont Actualités and Pathé-Journal also present "the universe's first living newspaper" before film screenings. Nahum did not force his customers to buy his films by the meter, as Pathé did. He rents out to fairground vendors short films of various genres, "burlesque, realistic, dramatic, religious and sometimes erotic", writes Dominique Missika in her lively, well-documented account. The book also contains numerous passages of a novelistic nature, when she recreates Nahum's monologues, thoughts, remarks, dreams and dialogues, allowing the reader to form a sensitive impression of the past.

The titles of the films have everything to attract a wide audience: Nos bons curés, Le petit Ménage, Le Concierge indiscret, Le Cireur boulevardier, Les Amours d'un collégien, Rêve d'une vierge, Le Masseur, La Gigolette parisienne... Nahum also rents out saucy films, shown in the countless brothels, basements and back rooms of cafés.

In December 1910, possibly the object of a denunciation, the three young associates were caught in Montmartre by the Paris police pimping squad as they were filming an "obscene" scene. The films were seized - later destroyed - and the boys were taken, handcuffed, to the police station under article I of the law of August 2, 1882, which punishes outrages against public decency. Senator Béranger, known as "father modesty", imposed a wave of prudery. Nahum and his friends were not the only ones to be arrested. His associates were sentenced to three months in prison, and Nahum to four, for "outrage to public decency", each fined 10,000 francs. He was punished more severely because he was not French. The authorities were even considering deporting him. But his wife, who was pregnant at the time and had adopted the name Marcelle, wrote to them. She asserted that her husband had made the films under duress, when he was employed in a photography store. Nahum Tanenzaph retained his residence permit, but remained a suspect in the eyes of the police services. This conviction would be exploited in a disproportionate, despicable manner by the magistrates of the Vichy government, and would play a decisive role in his tragic end. For the time being, Marcelle is having a miscarriage.

Rapid Film

In 1912, Marcelle and Nahum moved to rue Ordener and founded Rapid Film, a company with six workshops where they carried out "cinematographic work": development, printing, titles. Ciné-Gazette succeeds Ciné-Actualité and presents "life through the moving image":

"The vogue for the first sea baths, music-hall revues from the capital, the first aeronautical exploits, automobile races, and sometimes echoes of disasters or wars. Only authentic documents, unlike his competitors who have no qualms about reconstructing scenes after the fact in order to film them."

Nahum now calls himself Bernard Natan. He advertises in the trade press, and exhibitors are happy to show his films.

The Great War

On August 27, 1914, Natan, still legally Nahum Tanenzaph, enlists in the Foreign Legion. Joseph Kessel, Blaise Cendrars, Guillaume Apollinaire did the same. Nahum was assigned as a driver to the 19th Squadron of the Military Crew Train. During the Battle of the Marne and the fighting in Champagne, he drove trucks carrying soldiers to the front, supplying them with ammunition and food. He also evacuated the wounded under the shells and bombardments of the German air force. Poisoned by gas in 1916 at Prunay, he was twice cited in the 97th regiment's orders by General Bizot. Hospitalized for several months, he was then assigned to the Versailles motor pool, for the use of the Prefect of the Seine, and finally transferred to the Army's film section to counter German propaganda. On demobilization on October 11, 1918, Sergeant Tanenzaph was awarded the Croix de Guerre with palm. He appealed to the Paris Court of Appeal for his rehabilitation, which he obtained in 1919. The war, for the time being at least, erased his conviction. He was also granted French nationality.

In 1927, Nahum, who calls himself Théodore Natan, registers his company, Les Productions Natan. He is elected member of the Board of Directors and Treasurer of the Chambre syndicale de la cinématographie. John Maxwell, Sydney Garrett, Henri Diamant-Berger and Armand Handjian contribute funds. Natan produces La Châtelaine du Liban, Mon cœur au ralenti, Phi-Phi and La Madone des sleepings.

Natan, a producer, wanted to match those of Hollywood, where other Jewish immigrants had founded Warner and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Berlin's UFA also impressed him. At the foot of Montmartre hill, he bought premises at the corner of rue Bergerac and rue Francœur, where he set up studios and laboratories. He enlarged them by buying the buildings on rue de Bergerac. He tells La Cinématographie française magazine:

"When a director comes to see me, I supply him with all the blank film he needs, operators if he doesn't have his own, I develop, print and title his film, and so on. In a word, he's relieved of the care and expense of the whole material part of his work."

Bernard Natan launches a blockbuster, La Vie merveilleuse de Jeanne d'Arc, fille de Lorraine. Thousands of young girls, "brunettes who knew how to ride a horse", sent their photos to a jury of writers and filmmakers. Some of them shoot a short film. The film was directed by Marco de Gastyne on natural sets, with extras and horses recruited from the army. After this film and until 1935, Natan met with nothing but success.

La Gloire

Like Natan, Charles Pathé built an empire from nothing. Unlike Natan, he did not believe in the success of talking pictures. American studios, which were bringing star-studded talkies to France, gave him stiff competition. They built studios in Saint-Maurice, while the Germans set up studios in Épinay, where René Clair shot his first sound film, Sous les toits de Paris. After a long period of hesitation, Charles Pathé gave in to Natan's demands to join forces with him. He had to take out large loans from two bankers and pay a substantial commission to the intermediary.

In the early Thirties, Natan's rise seemed irresistible. He opened the French Film Office in New York on Fifth Avenue, in Rockefeller Center. Based on the American model, he hired stars on an exclusive basis: Charles Vanel, Gaby Morlay, Jean Gabin, Renée de Saint-Cyr. He chose the best directors: Raymond Bernard, Jean Grémillon, Marco de Gastyne, Maurice Tourneur. The "Cité industrielle du film" in Joinville, with its eight editing suites, is running at full capacity. The magazine La Critique Cinématographique devoted a special issue to it in 1930.

Marcelle gave birth to twin daughters. The family lived in luxury. In addition to their private mansion on rue Caulaincourt, Natan acquired a 17th-century manor house in Sologne (300 kilometers south of Paris), where he held sumptuous parties. He then commissioned architect Léon David to build an Arts Deco villa in Carqueiranne, near Hyères on the Mediterranean coast, and finally the "Villa Rose" in Ploudalmézeau, at the tip of french Brittany. A single key opened the door to all his properties.

With Roland Dorgelès

Natan produces an adaptation of Roland Dorgelès's novel Wooden crosses (Les Croix de bois), which narrowly missed out on the Goncourt prize against Marcel Proust's In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower (A l'ombre des jeunes filles en fleurs). The script was written by Dorgelès in collaboration with director Raymond Bernard. Five hundred extras took part in the filming, which took place not far from Fort de la Pompelles, the site of major battles. A special screening was dedicated to the veterans of the Dorgelès regiment. After the words "The End", they all exclaimed: "That was it!"

A gala screening is organized at the Moulin-Rouge, attended by Paul Doumer, President of the Republic, ministers, deputies, senators and ambassadors, as well as the Tout-Paris of the arts and letters.

The film is then shown in Belgium, in the presence of the King of the Belgians. Natan offers a sumptuous lunch to Belgian journalists and Pathé-Natan stars Victor Francen, Pierre Blanchar, Charles Vanel, and Marie Marquet, a member of the Comédie française. The film was even screened in Germany on May 8, 1932. But in 1933, the Nazis came to power and banned it.

More than seventy films were released by Pathé-Natan studios between 1930 and 1935.

The crash of 1929 hits France

The economic crisis causes many companies to go bankrupt, and banks pull out. Paramount closed its Saint-Maurice studios after losses of 8 million; Gaumont was liquidated with liabilities of 100 million. The Pathé share price plummeted, but Natan continued for a time to make profits from the sixty-two modern theaters he had built. However, the bankers he had borrowed from also found themselves in difficulty. To meet his creditors' demands, Natan increased the company's capital and issued bonds, but the proceeds were only half of what he had hoped for. The debts became impossible to repay.

Once adored, Natan became suspect. The financial press organized a campaign to destabilize him. In 1931, the financial prosecutor's office opened an investigation against him. An attempt was made to oust Bernard Natan. Maneuvers against him were hatched from all sides. In spite of everything, Natan prepared the premiere of Les Misérables at the Marignan-Pathé on the Champs-Élysées on February 3, 1934. A full house, the film was a success. Champagne was popping.

Three days later, Paul Morand published a satire, France la Doulce, in which he accused "foreigners" of invading "the national cinema": "Naturalized pirates who have made their way through the darkness of Central Europe and the Levant to the lights of the Champs-Élysées."

Likewise, Simenon: "The first Hungarian or Transylvanian to have the idea for a film is, of course, a production manager with a salary of twenty to thirty thousand francs a month, not including profits."

In the pages of Candide, a right-wing weekly newspaper, we read: "M. Natan from Jassy and other places, holds in his white handcuff the Joinville studios, seventy movie theaters in Paris and the suburbs, circuits in the provinces, the best actors, the best directors, a radio station (Radio-Vitus), a filmed newspaper, the Pathé-Journal, whose action is immense and inescapable, which can support or fight men and parties, political or social views, French or not French." Natan has become "a metèque".

Natan: "Jewish microbe"

In the press, Natan, in dire cash-flow straits, is called a swindler, a "Jewish microbe". Robert Dirler, a shady guy who pursues him with his hatred, declares: "It's the man I'm after! I'll kick him and his Moldo-Slovak and Turkish staff out of French cinema". A bizarre but tenacious phrase: Robert Kanters, a decade later, would use it in his turn when he said on a literary program that Romain Gary, who had just been awarded the Prix Goncourt for The Roots of Heaven (Les Racines du ciel), wrote "in Moldo-Vallachian". Gary punched him in the face in front of everyone at Lipp restaurant.

In 1934, the Alexandre Stavisky affair broke out. The far right naturally "ate some stateless Jew", in the anti-Semitic phrase of the day, while the far left vilified capitalism. Film studios are idling. Dominique Missika writes: "France would be invaded by a swarm of 'Balkan producers, well-intentioned indeed, if that means their intentions were to produce on our soil for personal profit'."

In 1935, the Seine Commercial Court appointed experts to examine Pathé-Natan's accounts. Léon Bailby insults "the Jewish swindler Tanenzaph". Juvénal, a pamphleteer's weekly, writes that Natan's invitations were once hoped for: "Nothing could be more repugnant than the rush of broadsheets on the man whose advertising budgets they were fighting over not so long ago." The rue Francœur studios were raided on April 18, 1935.

Natan was unable to rectify the situation. Charles Pathé, his former partner, did nothing to help him. Quite the contrary, he drove him into the ground, claiming to be his victim. On July 23, 1936, Pathé-Cinéma's bankruptcy was confirmed by the Court of Appeal. Natan was dismissed. All his companies went into receivership. In reality, the Pathé-Natan studios were not doing so badly, as filming continued on rue Francœur and in Joinville.

In France, the atmosphere is poisoned. Roger Salengro, Léon Blum's Minister of the Interior, accused of having deserted during the First World War, committed suicide by gas on November 17, 1936. Charles Maurras wrote in the far-right magazine L'Action française: "Léon Blum? A man to be shot in the back." In 1938, Natan was questioned by Judge Ledoux, along with his bankers. He set up a dangerous transaction worth 7 million francs in an attempt to keep his bank afloat.

The fall

On December 20, 1938, Bernard Natan was arrested like a thief in his mansion on rue Caulaincourt and taken in a cell van to the Santé prison. It was freezing in the cells. "After Natan's arrest, the press went wild against him", writes Dominique Missika. He never regained his freedom.

Requests for Bernard Natan's release were systematically rejected. The hearing was set for May 5, 1939. On May 12, 1939, only Roland Dorgelès, a member of the Académie Goncourt, took the stand to testify on his behalf. Prosecutor Étienne Baur's indictment was venomous: "A scoundrel of the most vulgar kind, whose career, which began in filth, ends today in scandal and shame." On June 2, Natan is sentenced to four years in prison.

Imprisoned at Fresne, Bernard Natan works in the library. When war broke out on September 2, 1939, he wrote tragically to the prison governor asking to join the French army. "I'm a very good electrician, I know glazing very well, and through my industry, I'm a photo and film technician." He was not allowed to enlist, even though he was a veteran and had been awarded the Croix de Guerre.

Pétain signs the armistice on June 17, 1940. The demarcation line divides France in two. Hatred of the Jews became state anti-Semitism under the Vichy government, with the promulgation of the law "concerning the status of Jews" on October 3, 1940. Jews became pariahs, excluded from society. They were no longer allowed to own a car, a bicycle or a radio, or to frequent cafés, restaurants, concert halls and squares: "Dogs and Jews forbidden", the law read at the entrance. They were no longer allowed to work. They were excluded from theaters, publishing houses and the film industry. Curfew was imposed from 8 p.m. onwards. Jews in the former Seine department were listed in the "Tulard file", and their identity cards bore the word "Jew" in red letters.

Created in March 1941, the Commissariat aux questions juives (Commissariat for Jewish Affairs) organized the liquidation of Jewish assets, appointed receivers and monitored their activities. Bernard Natan is registered in the Jewish census file. The Marignan-Pathé Theater, that Natan had built on the Champs-Élysées, is transformed into the Soldaten-Kino.

Natan is tried on appeal on May 30, 1941. He is filmed him in the defendant's box on July 4, 1941. In Le Petit Parisien, we read: "He has the mucky complexion that heralds all degradations." And in La France au travail: "His linen is as dirty as his soul, the forehead starts from the occiput and follows an insensible slope to the root of a long, thin, humpbacked nose that never stops stretching out a hint of scorched moustache, set against a poor, gaunt, narrow mouth."

Degradation

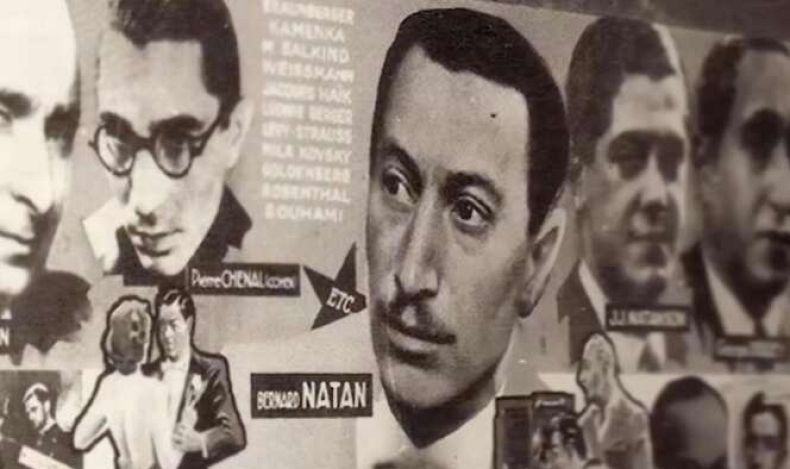

In September 1941, the "The Jew and France" Exhibition opened with great fanfare at the Palais Berlitz. On a large photo panel entitled "Les Juifs maîtres du cinéma français" ("The Jews, masters of French cinema"), we can recognize the face of Bernard Natan, who has been subjected to deplorable detention conditions for the past three years. The public is told how to recognize "the Jewish race": they have "large, massive, protruding ears, a fleshy mouth, thick lips, a protruding lower lip, a strongly convex, soft, broad-winged nose, soft features".

On March 11, 1942, Jacques Donnedieu de Vabres, rapporteur for the Conseil d'État, signed the decree stripping Bernard Natan of his French nationality. The announcement appeared in the Official Journal (Journal Officiel) on March 27, 1942. From the same month of March 1942, Jewish prisoners from Fresnes and De La Santé prisons were taken to the Drancy camp. Marcelle, who sheltered her two daughters in Brittany, never abandoned her husband. Whenever she gets permission, she goes to the visiting room to bring Bernard clean clothes and food. To tell him about her daughters.

With no illusions about his fate, he writes a farewell letter to his daughters Zouzou and Bécoto (Betty and Marie-Louise). "Never in life will you [meet] someone who loves you as much as she does, and who wants so much that you think your little mommy is your only and best friend to whom you tell everything, your sorrows and also your joys."

In May 1942, children aged six and over were required to wear a yellow star on their coat or jacket. The big round-up of Jews in Paris, carried out by the French police, took place on July 16 and 17, 1942. Filmmakers Marcel L'Herbier and Claude Autant-Lara are delighted by the anti-Jewish laws: "At last, pleasant working conditions, now that Jews and foreigners have been ostracized."

Auschwitz-Birkenau

Jews who have served their sentences are handed over to the German authorities. Officially liberated, they were taken to Drancy. On August 28, 1942, Bernard Natan became Nataniel Tanenzaph again. On September 21, 1942, he wrote his last letter.

"My dear mother,

Only a few lines, the mail has nothing for me, but I know you wrote to me because the last letter I received was from Thursday, so it's possible that tomorrow I'll receive two letters.

Mommy dear, I won't write tomorrow because the letter will reach you who knows when.

Hope and confidence, because that's the order, although from what I've been told, circumstances seem to be getting more and more difficult.

But trust and calm, the Good Lord will help us.

You and the dolls, from the bottom of my heart I give you a big hug."

On Wednesday, September 23, he and twenty-seven Jews board a truck that takes them to Drancy. Natan had been taken there "by the 5th section on the orders of the German authorities". Drancy was placed under the direction of SS Dannecker. Forty-eight hours later, Bernard Natan found himself in a convoy of cattle cars. It carried 1,444 people to Auschwitz-Birkenau. The elderly, mothers and children are gassed within hours of arrival. Only those able to work enter the camp.

Marcelle receives the "regulatory documents establishing her Aryan status". Her daughters were nonetheless called "little Jews" by their neighbors in Brittany when they returned home from school. Back in Paris, Marcelle found a letter in her box. It was written in Natan's hand, which reassured her. She was unaware that her husband had written it under duress, on the orders of the SS, in order to deceive the woman to whom it had been sent. Natan is finally murdered in Birkenau.

Bernard Natan's brother, Samuel Tanenzaph known as Émile Natan, was detained at the Miranda de Ebro Gestapo camp before joining the Free French Forces in 1943.

Inheritance and memory

Following the dispossession and elimination of Bernard Natan, new experts commissioned by Vichy examined Pathé's accounts, concluding that the company's assets exceeded its liabilities. Companies such as the Péchiney group, Thomson-Houston, Compagnie des compteurs, Lyonnaise des eaux and the Georges Descours group take possession of Pathé. The Francœur studios ran at full capacity, producing 16 films between 1943 and 1944. To name but a few: Pontcarral, colonel d'Empire, Monsieur des Lourdines, Falbalas, Les Enfants du paradis.

However, Marcelle's assets under sequestration were never returned to her. She had to wait until 1948 to receive the certificate attesting to her husband's deportation. Injustice was also perpetuated by reputation: all Cinema Histories, including that of Communist Georges Sadoul, peddled spurious accusations. Bernard Natan was systematically dragged through the mud. Before Dominique Missika, there was no one to rehabilitate him. Natan's work would have been wiped out, had it not been for the determination of his grandchildren.

"In June 1998, with the help of the association Les Indépendants du 1er siècle (The First century independents), a one-day manifesto was held at the Cinéma des cinéastes, avenue de Clichy". Bernard Natan's two daughters were there. Serge Klarsfeld took the floor. He told the story of his uncle Henry Klarsfeld, also from Romania, who became a filmmaker, chairman of Paramount and one of Natan's best friends.

In 2005, Natan Tanenzaph and his sister Marie's names were added to the Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial. In 2013, Serge Klarsfeld inaugurated a commemorative plaque in honor of Bernard Natan in the courtyard of the Fémis (National Film School), which has been housed in the rue Francœur studios since 1996. The plaque reads:

"Bernard Natan founded the famous Francœur studios here, around his Rapid Film company in 1920. He united the headquarters of Pathé-Natan, the leading film group of the 1930s. Bernard Natan died in October 1942 in Auschwitz-Birkenau."