Rebel, apostle, saint: Clare of Rimini offers a fascinating example of a woman who, in an era troubled by political rivalries, armed herself with radical faith to change the world.

* Lire en français

In a medieval Italy torn by bloody factional struggles, Clare of Rimini (c. 1260-1324/9) found refuge in a radical faith that fed apostolic rebellion. Following in the footsteps of St. Francis of Assisi, she embraced poverty as a way of changing the society of her time. Alongside other women, and not without facing adversity, she adopted an exuberant spirituality that mobilized all the senses in her struggle against the evils of the world.

On the occasion of the previously unpublished English translation of her Life, accompanied by a rich interwoven commentary, historians Jacques Dalarun, Sean Field and Valerio Cappozzo look back at the life of this powerful, rebellious woman.

What is the origin of the Clare of Rimini phenomenon? Who was at first this ordinary woman, if she was ever ordinary?

One of the first things that makes Clare interesting is precisely the fact that her early life is in some ways quite typical for a medieval woman, at least for a medieval woman from an elite family in an Italian city. She is at first under the control of her family: Her first marriage is arranged when she is quite young. She suffers hardships, including the loss of her mother, political exile, and then the deaths of her father and her first husband. Eventually she remarries, this time for love, to a handsome man with whom she enjoys a decade of satisfying married life. All of the pain and pleasure of medieval life is present in Clare.

What is the terrain (political, economic, religious...) in which the Clare of Rimini phenomenon flourished, that might help to explain it?

The political context in Rimini is an essential background to Clare’s entire life. Her family is exiled in the early 1280s, when the Malatesta family seize power in the city. When Clare and her family return around 1284, her father and brother are executed, and Clare and a surviving brother are once again forced to flee to Urbino. Clare’s personal religious conversion can be seen, in part, as her reaction to the challenges and complexities of political strife in an Italian city, and of the disastrous consequences of her family finding itself on the losing side of a political battle.

How does one become Clare of Rimini? What explains this movement of conversion, from a more conventional way of life to an exceptional one?

The Life of Clare portrays the moment of conversion as driven by a vision: The Virgin Mary appears to Clare, in the Franciscan church of Rimini, and urges her to abandon the world in favor of a life of penitence. When her second husband dies, she follows this visionary advice and makes this turn in her life. In one sense, Clare’s conversion is uncontroversial – any medieval preacher would have urged a twice-married widow to remain chaste and to embrace Christ, the eternal husband. But the extent to which Clare throws herself into extreme penitence sends her far beyond what a churchman would have counseled. Clare does nothing half way; if she will embrace penance, it will be in an extraordinary form that signals her complete turning away from food and comfort and physical pleasure.

What does it mean to become an apostle? What does this new relationship with oneself (renouncing the flesh) and with others (preaching) actually involve?

The radical nature of Clare’s project first becomes apparent when she joins her surviving brother in exile in Urbino around 1295. There she begins to beg in the streets, to make a public spectacle of herself that attracts both praise and criticism. Like the apostles, she has a public message to convey, and back in Rimini a few years later this begging begins to be combined with teaching and preaching to bring others to a similar life of penance. She suffers accusations of heresy, but perseveres to regains her good name and redoubles her efforts in this public mission; not just to live a life of penance herself, but to engage with the world and to change the ideas and behaviors and beliefs of those around her.

Is Clare of Rimini an isolated phenomenon? Did she have predecessors in the past, or "accomplices" in her own present?

Clare forms part of a larger movement, particularly active between Italy and the Rhineland and stretching from Marie of Oignie (d. 1213) to Catherine of Siena (d. 1380), in which women insist on participating in an active religious life. More specifically, she is spiritually similar to holy women from central Italy such as Margherita of Cortona (d. 1297), Clare of Montefalco (d. 1308), and Angela of Foligno (d. 1309), who are all supported or promoted by Cardinal Napoleone Orsini and his chaplain Ubertino of Casale, a “spiritual” Franciscan (the most radical wing of the Franciscan Order) whom Umberto Eco made one of the leading characters in his novel The Name of the Rose. But we have no evidence that these women were in contact with each other, except indirectly through the supporters they shared. By contrast, in Rimini, Clare stands at the center of a network of laywomen and nuns whom she publicly helps and with whom she has frequent spiritual conversations.

How did people react to this woman's decision to choose extreme poverty and preaching? Did society accept it? And the Church?

Beyond her extreme personal deprivations, Clare’s poverty consists mainly of begging for others (almost always for other women), and this charitable activity does not seem to cause too much scandal. Her public interventions, for example to save a woman’s husband who is threatened with mutilation by the tribunal of the Commune, gain the clemency of the Malatesta, her family’s old enemies who are now masters of the city. What bothers clerics and husbands the most – and what leads Clare to be accused of heresy – is that she teaches other women and forms them into a network parallel to the official church. The height of scandal is when she shows herself in the streets of Rimini, from Good Friday to Holy Saturday, half naked and having herself scourged with all the tortures of Christ’s Passion. It is Cardinal Orsini who brings this practice to an end, in 1306, by offering Clare a kind of deal: give up these public excesses in exchange for unofficial recognition of her little religious community.

Most people Clare speaks to are not very literate, and she herself relies heavily on images and the visual imagination. It's all very exotic for us moderns, who live constantly in texts and words. What is this "thinking through images" that is so important in oral societies, which are above all visual, sensitive societies?

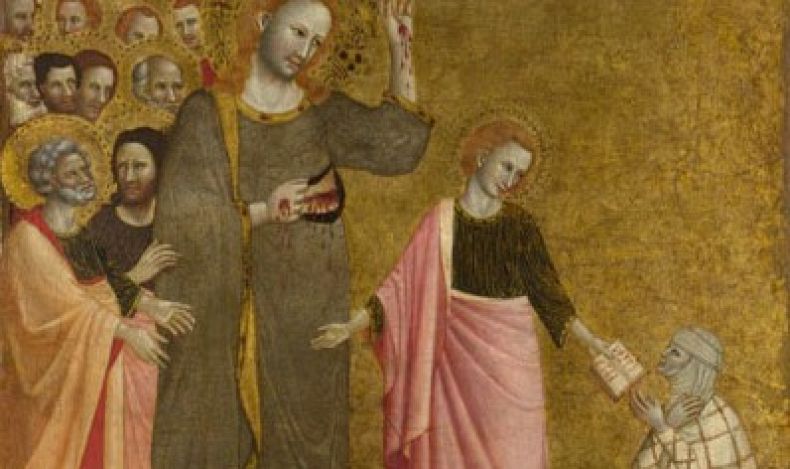

Medieval society places a high value on the written word precisely because not everyone can access it, and because the most important text, the Bible, guides Christian life. Clare, who cannot read or write, sees herself, in a vision, being given a golden book by John the Evangelist. The spirituality of these holy women is nourished by scraps of Scripture encountered (and sometimes misunderstood) in the liturgy, and indeed by images. Clare’s initial conversion is surely sparked by meditating before an icon of the Virgin. We have been able to show that her most famous vision (the one in which John gives her the book) is inspired by the frescos of the church of Sant’Agostino in Rimini. Lost in contemplation, Clare is overwhelmed by the power of these images, and she transforms them, in meditation, into visions that shape the essential turning points of her life. The vision of the golden book, recounted in the Life of Clare, is in turn the subject of two marvelous triptychs painted shortly after Clare’s death (around 1326).

Another exoticism: Clare's Christian world is full of "demons". What do these images represent? What use are they to those who see, name or show them?

Demons represent everyone's troubles, temptations, and weaknesses. Daily difficulties and their complications, it was thought in the Middle Ages, were full of demonic influences. To endure, one had to maintain a strong moral conscience, and in hagiographies demons are figures that serve to emphasize the constant dangers of the spiritual path. They are warnings not to give in, not to betray the faith, as in the last chapter of the Life, where we read that "God allowed that Sister Clare should be tempted by demons." These demons beset her sleep with constant nightmares, make her fall, cause her to lose a finger on her hand; but Clare accepts their presence, understanding that these are trials she must face. Thanks to her faith, the demons "suddently departed, ineffective." After enduring these difficulties, Clare arrives at illumination, reflecting her image in a mirror and radiating light, becoming, just as her name indicates, chiara (clear or clarified).

In the end, this apostle's life and preaching were indeed put down in writing, and the Life of Clare is no less surprising than "Clare’s life". What do you find the most surprising about the very existence of this text?

Three elements of this text are particularly surprising: the fact that it is a Life written while Clare is still alive, and which lacks the account of her death (added later); the fact that it is written directly in Italian; and, finally, the refinement of the vernacular Italian language, which is much more developed and harmonious than the chronicles or hagiographies of the time. Regarding Clare’s charachter, it is certainly striking how strong and dedicated she is, never content to remain passively spiritual or contemplative, but rather confronting the society of her time. Clare of Rimini suffers accusations of heresy and clashes with the politics of her commune, but she always manages to carry out her projects concerning the future of her community. This woman’s struggle with the preconceptions of her time helps us to understand late medieval Italy, and allows us reflect on the faith of ideals and the spiritual strength that helps overcome demonic difficulties, beyond which lies a source of light.